The Arctic is no longer a remote expanse beyond the edges of global commerce — it is now a contested arena where strategic competition, energy development, and maritime innovation converge. As climate change accelerates sea ice retreat, previously impassable waters are opening to navigation for longer periods each year. This change unlocks shorter trade routes, exposes massive untapped hydrocarbon and minerals reserves, and creates demand for ships able to operate in some of the harshest conditions on Earth.

In this evolving environment, icebreakers are more than just engineering feats — they are geopolitical tools. Nations that control them can escort commercial shipping, supply remote installations, and assert sovereignty over Arctic waters. What is now emerging, however, is a geopolitical contest between the seven Arctic NATO member states and Russia, alongside China—which, though not an Arctic state, is increasingly asserting its interests in the high north.

For shipbuilders, equipment manufacturers, and maritime service providers, these developments signal one thing: demand for ice-class vessels — particularly heavy icebreakers — is set to increase.

Geopolitical Context: Russia and China in the Arctic

For Russia and China, both aiming for dominant position in global trade and energy, cooperation in the Arctic offers economic and strategic benefits. Russia and China describe their relationship as a “comprehensive strategic partnership,” one that extends to the Arctic. But behind the diplomatic language and on-the-ground engagement lie significant differences in priorities, strategies, and trust levels.

China’s Arctic ambitions began to take shape in the early 2010s, motivated by its reliance on maritime shipping and energy imports. In 2013, after agreeing to respect Arctic sovereignty and navigation rules, Beijing secured observer status on the Arctic Council. Its 2018 Arctic white paper formally declared China a “near-Arctic state” and integrated the region into the Belt and Road Initiative as the “Polar Silk Road.” Officially, China emphasizes scientific research, environmental protection, and commercial activities — with no public mention of military ambitions. Russia, by contrast, treats the Arctic as a sovereign domain. Its priorities center on resource exploitation, military presence, and the Northern Sea Route (NSR) as a domestic shipping lane.

This divergence has historically limited cooperation outside of energy projects. Yet mutual needs have kept certain partnerships alive. After sanctions limited Western investment in 2014 and cut it off in 2022, Chinese financing became more vital for Russia’s Arctic oil and gas projects. In July 2023, the two countries launched a regular shipping corridor through Arctic waters, completing 80 voyages in its first year.

The Arctic LNG 2 project demonstrates the fragility — and resilience — of such cooperation. The $20+ billion venture was sanctioned by the United States in late 2023. China’s Wison New Energies announced its withdrawal in June 2024 under Western pressure, but by August, Chinese ships were covertly delivering massive power-generation modules to the Russian site, even changing vessel names mid-route to avoid detection.

The 13th China–Russia Arctic Workshop in October 2024 further revealed underlying differences. Russian participants emphasized military cooperation and resource development, while Chinese delegates prioritized energy and shipping routes alongside technological innovation. Both sides agreed that technology — from AI-based monitoring to submarine cable systems — will drive future cooperation, but Russia focused on carbon emission management, resource extraction, and economic development, whereas China stressed using technology to deepen its international Arctic engagement.

These differences matter for icebreaker collaboration — Russia sees them as tools for sovereignty and economic control; China views them as enablers of trade access and technological prestige.

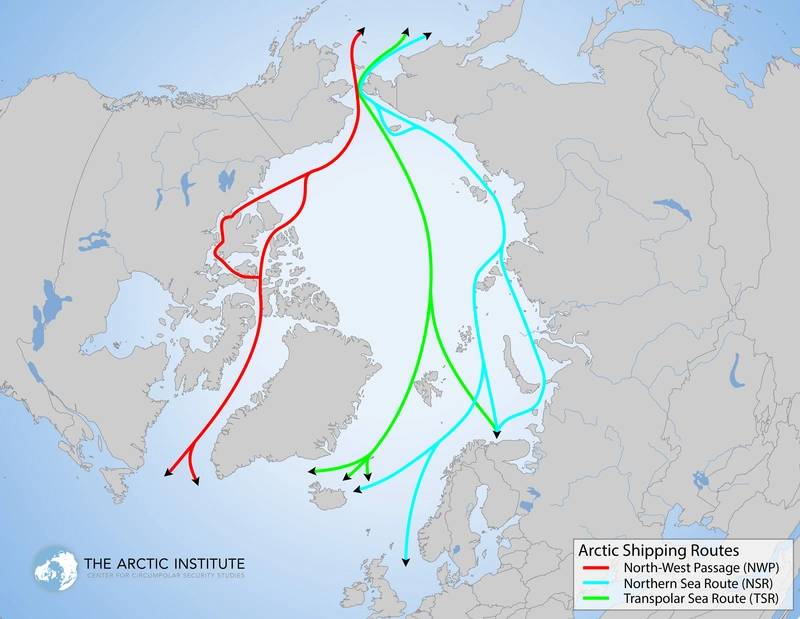

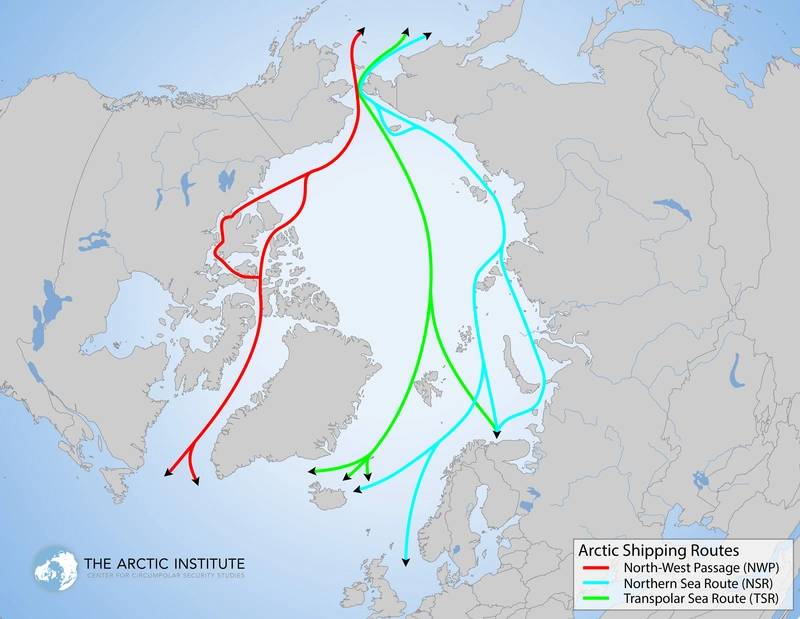

Arctic shipping routes.

Arctic shipping routes.

Copyright: The Arctic Institute & Malte Humpert

The Northern Sea Route and Infrastructure Push

The NSR runs the length of Russia’s Arctic coast — 24,140 kilometers (almost 15,000 miles) — linking the Barents Sea to the Bering Strait. In optimal conditions, it can cut travel time between Asia and Europe by up to 40% compared to southern routes.

Hence, for Russia the NSR offers market diversification and logistical opportunities, while also unlocking greater access to offshore Arctic resources and reinforcing its security, geopolitical influence, and economic development. For China, whose southern trade routes pass through U.S.-influenced chokepoints like the Strait of Malacca and Suez Canal, the NSR offers both strategic independence and economic efficiency. Access to Arctic hydrocarbons — estimated at 30% of undiscovered natural gas and 13% of undiscovered oil — is an added incentive.

But infrastructure alone cannot make the NSR viable year-round. Ice conditions still restrict navigation for much of the year. Russia has invested in ports, logistics hubs, and advanced navigation systems, but without sufficient icebreaker escorts, traffic volumes will remain seasonal. The NSR’s future as a commercial artery will ultimately depend on the pace of icebreaker construction.

Shipbuilding and Icebreaker Demand

Russia’s icebreaker fleet — the largest in the world — includes nuclear-powered Project 22220 vessels (Arktika, Sibir, Ural) designed to penetrate ice up to three meters thick at a speed of 22 knots in clear water, diesel-electric models, and aging Soviet-era ships. The next generation, expected to come online around 2030, will center on the massive icebreakers, designed to break through ice up to 4.3 meters thick and clear a channel up to 50 meters wide for extended navigation seasons.

Industry plans call for as many as 15–17 nuclear icebreakers to meet projected cargo volumes of 100–150 million tonnes, driven largely by LNG, crude oil, and metals exports from the Arctic. This will require sustained investment in new construction, maintenance, and repair capacity — areas where sanctions have already created bottlenecks.

Sanctions have slowed these ambitions — historically reliant on Finnish yards for high-end builds, Russia is now pushing domestic production, but delays linked to restricted access to Western propulsion systems, high-grade steel, and marine electronics have slowed progress. China has the industrial capacity to step in, but Moscow’s longstanding caution in transferring its nuclear propulsion know-how remains a point of friction. Cooperation has therefore focused on ice-class LNG carriers and conventional ice-capable cargo ships, areas where Chinese shipyards have proven capabilities and may expand into auxiliary systems, modular construction, and non-nuclear propulsion integration.

Outside the Russia–China axis, the West is also scaling up. In November 2024, the United States, Canada, and Finland signed the Icebreaker Collaboration Effort (ICE) Pact, pooling resources for Arctic and polar icebreaker development. At a March 2025 meeting in Helsinki, the partners outlined cooperation on design innovation, workforce training, and research and development.

Strategic Outlook

The Arctic icebreaker market is at the center of a broader strategic competition. Russia seeks sovereign control and resource dominance; China looks for diversified trade routes and a technological foothold; the West aims to counter both through alliances like the ICE Pact.

For the maritime industry, this “push–pull” dynamic presents both risks and opportunities. On one side is a Russia–China bloc developing icebreakers outside Western supply chains. Russia’s need to modernize and expand its icebreaker fleet ensures long-term demand for hulls, coatings, propulsion units, navigation systems, and cold-weather operational gear. China’s own ambitions under the “Polar Silk Road” will likely drive parallel demand for commercial and research icebreakers, supported by provincial-level shipbuilding initiatives.

On the other, Western-led initiatives such as the ICE Pact will compete for technological leadership, setting new design and performance benchmarks. This bifurcation of the market means suppliers in propulsion systems, ice-resistant materials, autonomous navigation, climate-adapted radar, and nuclear marine engineering could find demand on bothe sides — if they navigate export control regimes carefully.

In short, while the Russia–China Arctic relationship is not seamless, its very frictions may expand the overall icebreaker market by driving both states to invest heavily in parallel capabilities. For builders, component manufacturers, and service providers, the Arctic icebreaker sector over the next decade will be one of the few maritime domains where geopolitics, climate change, and industrial strategy align to sustain high-value demand.

Sources:

1.Carnegie Endowment

2.GIS Reports Online

3.World Nuclear News

4.Intelatus Global Partners proprietary data

5.U.S. DHS

6.Geopolitical Monitor

7.ScienceDirect

8.Oxford Institute for Energy Studies